Mario Hamlet-Metz

Barcelona and Milan, two bastions of opera

Photo© A Bofill/Teatro Liceo

A couple of weeks ago, the passion for opera was relived once again in two European theaters of great tradition, Barcelona’s Liceu and Milan’s La Scala. In the Catalonian city, the presence of Peruvian tenor Juan Diego Flórez singing his first Edgardo Ravenswood, the unhappy lover of Lucia di Lammermoor, was awaited with huge expectations and made the prices of the already expensive tickets soar to unheard heights. In the Lombard capital, the opening of the season, traditionally on December 7, always constitutes a national socio-cultural event, with an audience filled of politicians, members of the diplomatic corps and of the social elite and personalities of the world of the arts and fashion; these distinguished guests occupy most of the places in the beautifully renovated auditorium and leave little room for the “real opera fanatics”, who are seated—and heard--in the two upper galleries. Here too, it was harder than ever to get a ticket, given the fact that the opera to be performed, Verdi’s Giovanna d’Arco, was revived after an absence of 150 years and, no less important, that the protagonist would be the much admired Anna Netrebko. In both cities the events were highly publicized and an electric atmosphere of anticipation invaded the air.

Photo© A Bofill/Teatro Liceo

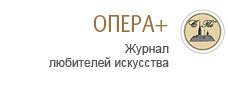

In 1835, two materpieces of bel canto premiered: in January, Bellini’s I Puritani, at the Théâtre des Italiens in Paris, shortly before the death of the composer, and in September, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, at the Teatro di San Carlo, in Naples. The role of the tenor was written for Gilbert Duprez, the creator of the “Do di petto”, who, by all accounts, was a lyric tenor with an extension to the higher register, which he was able to produce in an unprecedented stentorian manner. Flórez was, is and will always be a light lyric tenor, unsurpassable in Rossini but less ideal in other type of repertory that calls for a more robust middle register than his in order to solve the problems that may arise with heavier orchestration, voluminous voices or expressivity. For instance, in the tower scene (which so many tenor refuse to sing in the theater) and in the one that follows it immediately, when Edgardo irrupts into the room where Lucia has just signed the wedding contract with Arturo Bucklaw, Flórez’s sound was a bit thin and did not have the power to create the desired impact. He redeemed himself, for the most part, in the final scene, sung with impeccable elegance and style, even though here too, one would have wished a larger variety of colors in the sounds coming from his privileged vocal instrument. All in all, let us say that we appreciated the effort more than the final result. Never mind. The audience saw, heard, admired and applauded vociferously for a good twenty minutes. The Rumanian soprano Elena Moşuc did everything what the score and the stage director demanded of her aptly, without necessarily generating much sympathy or compassion for the mentally unstable Lucia. Marco Curia was making his debut at the Liceu and proved to have the right light baritone for the role of the manipulative Enrico Ashton, and the reliable Simón Orfila succeeded in injecting a good dose of personality into the character of Raimondo. Marco Armiliato gave a routine, unsubtle reading of the score, which at times was too loud and at others, too fast. The production came from Zurich, was signed by Paolo Fantin (sets), Damiano MIcheletto (staging) and Carla Testi (costumes) and, without being offensive, it did manage to raise some eyebrows. A big, leaning transparent Neon lighted three-story high tower made of clear metal and glass occupied almost half of the stage. It was a symbol representing Lucia’s imprisonment; in it, soloists sang and moved before doing it outside of it, where a few furnishings suggested interior or exterior spaces in the Ashton residence or in the Ravenswood cemetery. At the end of the Mad Scene, Lucia runs to the third floor and throws into the empty space towards her death and liberation. (Don’t worry, a puppet did it for her!) At the sound of the harp that announces the entrance of the already somewhat disturbed Lucia in Act I, we saw a lady all dressed in white coming on stage holding a bucket, another symbol, that of the fountain and of the “amata donna” killed by her jealous enraged lover. From that moment on, this ghostly figure will always be present, walking at a slow pace, seemingly participating in the action: she offered a dagger to Lucia when the character considers committing suicide at then of the duet with her brother; she showers with flowers the heroin during the wedding ceremony and Edgardo when he is about to lose his life. When both of them are dead, the lady-ghost seemed to be satisfied of having accomplished her revenge. So there!

Photo© Teatro La Scala

Ten years had gone by between the premier of Lucia di Lammermoor, in September of 1835 and that of Giovanna d’Arco, in February of 1845. In that period of time, a lot had changed in the Italian opera world. Bellini had died, Donizetti had composed his last work in 1843 (Dom Sébastien) and Rossini was enjoying the pleasures of the table in his Parisian residence in Passy, having stopped composing for the theater after his Guillaume Tell had left him exhausted in 1829. The sighing melodies of the early romantic era where being replaced by equally beautiful and contagious, albeit more aggressive ones that frequently contained idealistic or patriotic overtones. The heroines were no longer called Elvira, Amina or Lucia, but Abigaille, Odabella and Giovanna, and the primadonnas were now la Strepponi, la Loewe and la Frezzolini instead of la Grisi, la Pasta or la Tacchinardi. In other words, Verdi had arrived on the scene, and in his capacity as a genius still in the training stages, he knew to use tradition and innovate at the same time. In no other of his early operas belonging to the “Galley years” period was the past used so brilliantly (music of Guillaume Tell, La sonnambula, I puritani, as well as a few Donizetti concertati are easily recognizable) and the future outlined so clearly. In Giovanna d’Arco, the leading role of the chorus becomes evident; the orchestration and characterization begin to show signs of detailed craftmanship and maturation; the writing for the tenor announces from afar the parts of Rodolfo and Riccardo, in Luisa Miller and Un ballo in maschera; the father-daughter relationship is shaping up as one of the composer’s favorite themes, which will be fully developed in Luisa Miller, Rigoletto and Simon Boccanegra.

One of Giovanna d’Arcos melodies, the one that says “Tu sei bella, pazzerella” (You are beautiful, madcap) became so popular that in a few weeks it could be heard all over the peninsula played by street organ grinders. The lyrics, that describe the girl as being a bit out of the normal, is sung by the evil spirits that torment her mind with the worst intentions; this, in conjunction with Giovanna’s own words “La mia mente va smarrita” (I am losing my mind) said during the duet with Charles VII, seem to have inspired the dramatic concept of the Moshe Leiser/Patrice Caurier production. During the overture, the curtain raises halfway up and one sees the girl asleep, surrounded by agitated nurses or nuns and a vigilant father, in a room that looks and feels like a psychiatric institution. The bed and the statue of the Virgin will be the basic, permanent elements, and the whole story will be treated as a dream/nightmare, a very pragmatic way for the stage directors to solve the numerous problems of credibility in the implausible plot: a fanatic, bigoted father that questions his daughter brutally, accusing her of being dishonorable and sacrilegious; a king that falls in love with the warrior visionary girl who saved his life and her country twice; a heroine that is torn by conflicting feelings between duty and filial love and between the love for her king and a mission assigned to her by God. At times, the walls of the room disappeared and one saw, in the upper part, a series of murals depicting war scenes, while in the lower part, the chorus, fourth protagonist of the opera, advanced to the center of the stage, sang arousing war songs, or alternated praises with accusations that confused the already confused girl even more! One could also see a small-scale reproduction of the Cathedral of Reims, and the king with his hair, skin, armour and horse all gilded, in the manner of medieval illuminations, as well as the nowadays omnipresent projections designed by Étienne Guiol, which contributed to give some life to both the simplistic sets of Christian Fenouillat and the rather colorless costumes created by Agostino Cavalca.

Photo© La Scala

Anna Netrebko was at her best, vocally and dramatically. This is an artist that, the more you see her and listen to her, the more you admire her, for the courage and determination with which takes on new challenges, for the naturalness and spontaneity of her singing and for her undeniable attractiveness and charisma. Her voice went with much ease from the soft to the agitated and exalted depending on what kind of dream she was having or what kind of action she was undertaking, as a tempted enamored subject or as an army leader, and it was heard loud and clear over the orchestra, chorus and other soloists. As Charles VII, Francesco Meli’s nice timbre and good musicianship served him well to successfully handle the challenge posed by Miss Netrebko, a formidable subject. Devid Cecconi, the baritone who was called in to replace the ailing Carlos Álvarez, started hesitantly but improved as the evening progressed. The orchestra was in the expert hands of Riccardo Chailly, great admirer of this score, which, since he first conducted it in Bologna, in the late 1970’s, he has come to know in depth. All those involved followed his baton attentively. The la Scala chorus continues to be unequaled in this repertory.